Aviation of World War II

|

Aviation of World War II |

|

|

Soviet Union | Lend - Lease | Facts | Forum | Germany | Japan | R A F | U S A A F | Other | Photos |

|

Facts | People | Engines | Aces | Aircraft Handbook | WWII Periodicals | Contact | |

From BMW VI to M-17On Search of an Engine

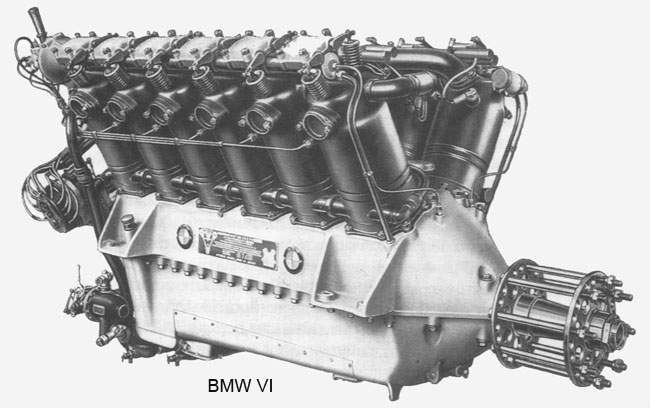

Soon after the Junkers concession enterprise in Fili was set up it became evident that hopes for a rapidly developing an aircraft engine industry based on this concession were not justified. Therefore, when in late 1923 the famous German company Bayrische Motorenwerke (BMW) proposed establishing production of its engines in Russia, the idea met with approval. Here is the opinion of the All-Union Council of the National Economy leadership on this question (February 4,1924): "As is known, the Junkers firm is obliged by the concession agreement to organize this (aircraft engine) production. Owing to recent friction surrounding implementation of this agreement, certain apprehensions arose as to whether production would be organized properly. Therefore, taking into consideration this circumstance, the BMW offer is very interesting and timely". BMW representatives, including General Director Popp, came to Moscow to discuss specific forms of cooperation. The Germans offered technical aid in founding a modern plant to produce BMW engines in Moscow or Petrograd. Our plans were more modest—set up a mixed company or acquire a license to produce the engines at an extant plant. A variant calling for BMW participation in the work of the Junkers concession was also considered. But, interest in the BMW proposal soon vanished. The firm's best engine, the BMW IV, had undergone testing at the Scientific Aircraft Engine Institute (NAMI) in Moscow. Its actual power was estimated at just 230-240hp, instead of the 300hp claimed. Young engineer V. Ya. Klimov, who later became an academician and designer of many famous aircraft engines, led the testing program. In addition, after the Western countries lifted the economic blockade in 1924, the USSR began producing American 400hp Liberty and French 300 hp Hispano-Suiza 8Fb engines (we designated them M-5 and M-6, respectively). The "engine hunger" was partially overcome. Some hopes in regard to Junkers remained, too. It promised to begin making its new L-5 engine at the Fili plant. "The All-Union Council of the National Economy Concession Committee considers it proper to suspend negotiations with BMW regarding technical aid in producing aircraft engines...," a document dated December 22, 1924 stated. By the autumn of 1925. the situation had changed. The Soviet government decided to cancel the Junkers concession and there was no hope left that it would help in engine production. The M-5 and M-6 engines no longer met modern requirements (this is not surprising since the Liberty; the prototype of the most powerful Soviet M-5 engine, was designed during the First World War). The following decision was adopted at a joint meeting of Air Forces and industry representatives on October 19. 1925: "To recognize as definitely desirable the attraction of first-class foreign engine manufacturing companies for both technical assistance and immediate work in the USSR". The government tasked the Engineering Department of the Soviet Trade Representative Office in Berlin "to probe" the capabilities of German engine building companies. In its reply prepared in early 1926, it reported: We got in touch with the Daimler firm, which unites Mercedes and Benz plants... The aforementioned firm has not engaged in aircraft engine production since 1918 and comparatively lags behind where design is concerned. Therefore, it can hardly be of interest to us regarding technical aid to Aviatrust in aviation engine building. ... As for the Maybach firm, the information we have suggests that its plant is building only engines for airships and its latest achievement was a 420hp engine made in 1924 for the Zeppelin that made a flight to America. Thus, the Maybach plant is not able to provide direct technical assistance to our plants interested in the production of aircraft engines. ... BMW remains the firm most interesting to us. One must add that the company had begun series production of the new V-12 water-cooled 500hp BMW VI engine by 1926. It had the important advantage of being a high-altitude engine, i. e. it could preserve its power in the process of climbing to altitude, whereas ordinary engines rapidly lose power due to reduced air density: This quality was achieved because the engine was designed to deliver full power (500hp) at altitude rather than on the ground. Its power was higher on the ground (by around 30%). but this regime could be maintained only for a very short time. In other words, the engine was created with "reserve power," which could only be realized at altitudes. This type of high-altitude engine was dubbed "oversized". Appearance of the BMW VI immediately attracted the attention of specialists in the USSR. Aviatrust managers wrote the following in this regard: The most powerful engine produced at Aviatrust plants is a copy of the American 400 hp Liberty - known here as the M-5. This is not a high-altitude engine, so its power at an altitude of 2000 meters does not exceed 200hp. Requirements levied on a modern aircraft engine are significantly higher. It must deliver at least 400hp at an altitude of 3500-4000 meters. An engine with this power is to be installed in a series of airplanes destined to enter the inventory in the near future: powerful fighters, a reconnaissance aircraft, and a bomber. After careful consideration of an engine satisfying the aforementioned requirements, the BMW VI, which can deliver 600hp on the ground, was chosen. The BMW VI engine meets Air Forces Directorate specifications regarding both power and operational performance. This engine presents less difficulties from a production standpoint than any other. A delegation comprising Aviatrust Board member I. K. Mikhaylov and Glavmetall representatives D. F. Budnyak and E. A Chudakov went to Germany in February 1927 for talks with BMW. On February 4th. the Soviet Trade Representative Office in Berlin reported the following: "The commission that Comrade Budnyak headed conducted an inspection at the BMW plant in Munich. The team unanimously concluded that we can limit ourselves to buying a license for the BMW VI, because the firm's achievements in other spheres of technical assistance do not offer us anything of value". In the course of the negotiations, it was learned that electrical equipment and some engine components were produced by other German firms rather than by BMW. For example, the crankshaft production method was a Krupp secret. However, these problems were solved and, on October 14, 1927, BMW General Director F. Popp and Aviatrust Board Chairman M. G. Urivayev signed a license agreement on BMW VI engine production in the USSR" According to the agreement, BMW granted our country the right to produce BMW VI engines at any plant in the USSR for 5 years. BMW also promised to provide consulting services in establishment of engine production and, in the event of necessity, send its engineers to the USSR to assist. Another stipulation was that the firm would inform the Soviet side about all improvements in its engines. For this, the Soviet side paid lump-sum compensation of $50,000 and, in addition, deducted 7.5% of the cost of every engine produced in the USSR. After that, Aviatrust signed an agreement with the Robert Bosch Electrical Company in Stuttgart for technical assistance in production of magnetos and spark plugs for aircraft engines (Plant No. 12 in Moscow was to produce them). The company also agreed with Krupp to purchase crankshafts and bearings for the BMW engine. |

|

|

|

Engines Articles | Designers | AM-35A/37 | AM-38 | M-105 | VK-107 | ASh-82 | BMW VI - M-17 | BMW 801D | NK-12 | Engine Maintenance Manuals Rolls-Royce Merlin | Rolls-Royce Merlin 25 | |

|

State Aviation Plant No. 26 in Rybinsk was chosen for the production of German engines. It was called Russian Renault until 1917 and wTas engaged in aircraft engine assembly using parts imported into Russia from abroad. After the BMW agreement was signed, the plant was modernized and expanded so that it could produce up to 500 engines annually in peacetime and 1000 engines a year in time of war. Its production area had reached 62.000 square meters by 1930, making it one of the biggest engine building plants of its day Housing was built near the plant for the German specialists participating in the establishment of BMW VI production. Preparations for production took a lot of time. Voroshilov was uneasy when he wrote to Stalin in December 1929: "On October 14,1927 at our insistence and choice, Aviatrust signed a license agreement to produce in our country a modern BMW VI engine, which had undergone testing in early 1926. More than 2 years have passed, but we have not received a single series-produced engine from Aviatrust. A small batch of 10 engines only recently was produced for delivery. Besides, the most important parts such as crankshafts and rollers (bearings) are not produced here at all. We buy them from Germany and it has only been since August 1929 that Aviatrust has been receiving technical assistance in this regard from Krupp. Also, the production of magnetos has not started yet... This BMW VI engine, the newest engine available in 1927. in the 2 years spent in the preparation process risks becoming obsolete before we can even introduce it into the air fleet". The BMW VI, which we designated the M-17, entered series production in 1930. That year. 165 engines were produced, with 679 manufactured in 1931. Production figures continued to rise in later years. About 100 German engineers and workers participated in M-17 production. Among them were people who previously worked with Junkers-Hennig, Domack, Eichler, a metallurgist named Ebeling from Brandenburg, and others. M. Brenner headed the plant's Foreign Department. When a Prof intern employee named Brandt visited the plant in 1932, many German specialists complained to him about low wages (300-450 rubles a month), bad food, and the insufficient level of production technology. At the same time. Brandt sensed from these conversations that many of them, being adherents to Communist ideas, sincerely tried to help in developing the Soviet aircraft industry: A German team of foundry' men even introduced a new improved method of casting components and communist F. Wolfram, a metal worker from Berlin, informed Brandt about cases of German espionage when the Reichswehr sent military men disguised as specialists to the USSR. As the production of M-17 engines grew, it was upgraded and its service life increased from 100 to 300 hours. It was the most widespread aircraft engine in the USSR in the 1930s. In all, 27,534 M-17 engines of various modifications were produced. It was installed in 1-3 fighters. R-5 and R-6 reconnaissance planes, TB-1 and TB-3 bombers, MBR-2 and MBR-4 flying boats. P-5, PS-9, and PS-89 passenger and transportation planes, and in a number of other Soviet airplanes. It was in service up until 1943. A variant designated the M-17T was employed in tanks. Using the M-17 as the foundation, designer A. A. Mikulin created the more powerful M-34, the first Soviet series-produced water-cooled engine. It was used on many aircraft of the pre-war period. In particular, it was installed in the ANT-25 that made a number of successful flights over the North Pole to the United States. Purchases of Heinkel aircraft and acquisition of BMW licenses were the last major events in the history of Soviet-German economic ties in the sphere of aircraft and engine construction in the 1920s and 1930s. As the German pro-Western policy intensified, relations between our countries cooled off. Moreover, by the early 1930s, desires for a military and technical union receded. Germany, feeling that the West more and more often "shut its eyes" to Versailles Treaty violations, little by little began developing its military aviation. The USSR managed to restore its economy wrecked by war and revolution and its leadership relied on the country's own resources for development of aviation and on cooperation with the USA and France. In the 1930s, Germany's participation in the Soviet aircraft industry boiled down to the work of individual German specialists at Soviet enterprises. Some remained in our country after the Junkers plant in Fili closed down, others came to work on contract terms. The latter approach was encouraged. During a 1932 Bolshevik Communist Party Central Committee session, the following special resolution on this matter was adopted: 1. Attract German aviation specialists. 2. Establish a fund in the amount of $7,000. 3. Task the Mossovet to allocate 50 rooms for foreign civil aviation specialists... Besides the rather large group of Germans at Engine Production Plant No. 26 in Rybinsk, in the early 1930s German engineers worked at other aviation enterprises and organizations of our country; mainly in the Civil Air Fleet system. At Aeroflot invitation, K. Berstecher, F. Mueller, W. Straus, O. Schreider, and A. Hobein worked at the Civil Air Fleet Main Directorate. Among Aircraft Research Institute employees one encountered the names of such engineers as E. Gra and W Fuchs (the latter was an electric welding specialist). Engineer-Designer W. Straus, Designer-Technologist G. Wersch, and Engineer-Designer E. Levy were at the Aircraft Engine Scientific Research Institute in Moscow. The Special Services Scientific Research Institute employed radio engineers H. Wachsmann and G. Schlossberg, F. Melchoir worked at Aviation Plant No. 82, an engineer named P. Frommholtz at Aviation Plant No. 85. German engineer R Daniel, F. Zucker, and W. Schtratman were among the foreigners working with the USSR Civil Air Fleet. A German specialist earned an average of 600 rubles a month, the normal level for Soviet qualified specialists. True, part was paid in foreign currency. One finds an interesting fact in A. P. Krasil'nikov's Planery SSSR [Gliders of the USSR]. A German named Josef Emmer, who worked at the Saratov Combine Harvester Plant, had built an E-3 training glider of the German Hercules glider type in 1932. At the VIII All-Union Glider Contest in the Crimea, he reached an altitude of 1945 meters during one of his flights, thus surpassing the world two-seat glider record. ANT-25Record AircraftTupolev

By 1926, BMW launched serial production of a new V-shaped 12-cylinder water-cooled engine, the BMW-VI, with a rated power of 500 hp. An important advantage of this motor was that it was high-altitude, i.e. it could maintain power as it rose to a height, whereas with conventional motors, due to a decrease in air density at altitude, the power quickly decreased. This property of the BMW-VI was achieved by the fact that when designing it, the operating mode at full power (500 hp) was taken at altitude, and not at the ground. In ground conditions, more power was obtained (by about 30%), but this mode could only be used for a very short time due to engine overload. In other words, the motor was created with “reserve power”, which could only be realized at altitude. In January 1927, a special delegation of Aviatrest board members and Glavmetal representatives left for Germany to negotiate with BMW. They inspected the production of aircraft engines in Munich. The Soviet trade mission in Berlin reported on February 4: “The commission... inspected the BMW plant in Munich and unanimously came to the conclusion that we can limit ourselves to only purchasing a license for the BMW-6 engine, since the company’s achievements in the rest of the technical assistance They won’t give us anything valuable.” With the last conclusion, the members of the Soviet commission, as we will show below, clearly got excited. Nevertheless, on October 14, 1927, the general director of BMW, Franz Popp, and the chairman of the board of Aviatrest, Mikhail Uryvaev, signed an agreement for the licensed production of BMW-VI aircraft engines in the USSR. State Aviation Plant No. 26 in Rybinsk was chosen for the production of German engines. Until 1917, it was called “Russian Renault” and was engaged in assembling aircraft engines from parts supplied to Russia from abroad. After concluding an agreement with BMW, the plant was modernized and expanded so that it could produce up to 500 engines per year in peacetime, and in case of war - 1000 engines annually. Although the commission’s conclusion dated February 4, 1927 stated that “the company’s technical assistance will not give us anything valuable,” about 100 German workers and engineers took part in establishing the production of aircraft engines. A comfortable village for German specialists was even built next to the plant. The German foundry team introduced a new, more advanced method of casting parts. In December 1929, People's Commissar Voroshilov wrote with alarm to Stalin: “On October 14, 1927, Aviatrest, at our insistence and choice, concluded a license agreement for the installation in our country of production of a modern BMW-VI engine, which had left the experimental stage at the beginning of 1926. More than 2 years have passed, but we have not yet received a single production engine from Aviatrest: recently only a small series of 10 engines was presented for delivery... The newest BMW-VI engine in 1927 is in progress introduction into production within 2 years risks becoming obsolete before we supply it to the air fleet.” Finally, serial production of the BMW-VI, which we designated M-17, began in 1930. That year, 165 engines were produced, in 1931 - already 679. Subsequently, the production volume continued to increase. Based on the M-17 engine, designer Alexander Mikulin (by the way, a student of the father of Russian aviation, Nikolai Zhukovsky, to whom Mikulin was his maternal nephew) created a more powerful water-cooled M-34 engine. It was used on many pre-war aircraft. They also installed it on the ANT-25. At the end of 1936, by order of Stalin, Valery Chkalov flew on this plane from Moscow to Paris, to the International Aviation Exhibition, and showed it to visitors there. “Let the Europeans marvel at the results of the Soviet aviation industry,” Stalin admonished him. The ANT-25, equipped with an M-34 engine, carried out the famous flights to America via the North Pole. The famous Chkalov crew had no complaints about the operation of the engine, created according to the German model. In 1936, after A.N. Tupolev assumed the position of chief engineer of the GUAP NKTP, work began on installing AN-1 diesel engines on the ANT-36. To install the AN-1 diesel engine, they chose an aircraft with serial number 188 - the last one rejected by the military mission. The modifications consisted of making a new motor mount and changing the alignment. This plane had a whole bunch of defects. In particular, the plant was unable to install a retractable landing gear. Flight tests of the RDD, begun on June 15, 1936, showed that the flight range with a diesel engine should increase by 20 - 25 percent compared to an aircraft equipped with the M-34R. In 1937, the aircraft that were in service were mothballed. They were remembered a year later. On December 20, 1938, a resolution was issued by the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks on conducting a long-distance record flight on a RD aircraft with a female crew. On January 7 of the following year, People's Commissar of Defense Voroshilov held a meeting on this issue, where the entire crew consisting of Nesterenko, Berezhnaya and Rusakova met for the first time. However, after a month and a half, pilot Berezhnaya dropped out of the crew and Mikhaleva was invited instead. The duties of the navigator were assigned to the test pilot of the Air Force Research Institute N.I. Rusakova. For the flight, the two best production aircraft No. 1813 and No. 1814 were chosen. Based on the results of an examination of the condition of the aircraft, Voroshilov made a report to the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, Molotov, which said in particular: "... Due to the fact that these aircraft have a number of design and manufacturing defects and are insufficient for "The capacity of the tanks for the intended flight requires their fine-tuning and additional equipment." While there was a discussion of issues related to the modification of the ANT-36 for the flight, the crew began training flights. From a conversation with Nina Ivanovna Rusakova and based on my acquaintance with the documents, I concluded that many issues related to preparations for the flight were resolved without the participation of the crew. There were even plans for training on the BOK-7 and BOK-11 stratoplanes, the existence of which the crew did not even know. In the end, apparently fearing negative consequences, they refused to re-equip the taxiway, and it was decided to carry out the flight itself on a more modern DB-3 aircraft. ANT-36 (DB-1)Long-range bomber

ANT-36. Military designation “Long-Range Bomber First” or DB-1, developed at the Tupolev Design Bureau by the design team of Pavel Sukhoi based on the ANT-25 RD aircraft. Produced in a small series and entered service with the Red Army Air Force. The plane had a maximum speed of 200 km/h and a bomb load of 1000 kg. The military version retained the airframe design, power plant and cabin layout from the prototype. The bomb bay was supposed to accommodate 10 bombs weighing 100 kg each. Machine guns were located in the cabins of the second pilot and navigator. The bomber was to be equipped with an aerial camera. In 1934 the airplane went into production. The airplane had a smooth skin and a full set of bomber and machine gun armament. The first plane was tested in the fall of 1935, but the customer refused to accept it because of poor workmanship. Factory no. 18 produced 18 airplanes of this type, of which the military in 1936 received 11 machines and 2 - in 1937. Only 10 of them were put into service, three were transferred to test centers, and the rest remained at the plant. In 1937 all DB-1 airplanes were mothballed. In the future, all manufactured DB-1 airplanes were used as targets on the test range.

In 1937, the aircraft that were in service were mothballed. They were remembered a year later. On December 20, 1938, a resolution was issued by the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks on conducting a long-distance record flight on a RD aircraft with a female crew. On January 7 of the following year, People's Commissar of Defense Voroshilov held a meeting on this issue, where the entire crew consisting of Nesterenko, Berezhnaya and Rusakova met for the first time. However, after a month and a half, pilot Berezhnaya dropped out of the crew and Mikhaleva was invited instead. The duties of the navigator were assigned to the test pilot of the Air Force Research Institute N.I. Rusakova. For the flight, two best production aircraft were chosen, No. 1813 and No. 1814. Based on the results of an examination of the condition of the aircraft, Voroshilov made a report to the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, Molotov, which in particular said: "... Due to the fact that these aircraft have a number of design and manufacturing defects and the capacity of the tanks is insufficient for the intended flight; they require further development and additional equipment.” While there was a discussion of issues related to the modification of the ANT-36 for the flight, the crew began training flights. From a conversation with Nina Ivanovna Rusakova and based on my acquaintance with the documents, I concluded that many issues related to preparations for the flight were resolved without the participation of the crew. There were even plans for training on the BOK-7 and BOK-11 stratoplanes, the existence of which the crew did not even know. In the end, apparently fearing negative consequences, they refused to re-equip the taxiway, and it was decided to carry out the flight itself on a more modern DB-2 aircraft. Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||